We Are Not Alone In Feeling Lonely

How the Pursuit of Individualism Has Driven Us Apart and the Potential for Loneliness to Reconnect Us

“When I get home now, it’s just silence.”

“Sometimes, being isolated makes me less lonely—compared to when I’m seeing what everyone else is doing on social media.”

“I’m tired. I’m lonely. I've landed yet another professional pursuit that feels hollow and meaningless in its ability to feed my soul.”

This is what loneliness feels like to some of the people I’ve talked to recently. In starting this newsletter, I hope to learn about many more uniquely different experiences that make the beauty of loneliness. So if you’d like to tell me yours, I’d love to hear it. And thank you, for being here with me.

So what is loneliness?

Here’s what ChatGPT responded:

“Loneliness is a complex and multifaceted emotional state that arises from a perceived discrepancy between a person's desired and actual social relationships. It is often characterized by feelings of isolation, emptiness, and a sense of being disconnected from others. Loneliness can occur even when a person is surrounded by others if the quality or depth of the social connections is lacking.”

Not bad! It makes an important distinction: even if you’re surrounded by people you care about and who care about you, you can feel lonely. Social isolation, as an objective, physical situation, is not equivalent, though they often affect one another.

Let’s add another layer: loneliness is an emotional state—and therefore one of the mind and brain, and deeply rooted in us. In one study, Livia Tomova, a research associate in neuroscience at the University of Cambridge, compared the feeling of hunger to the feeling of loneliness, suggesting it’s the basic need for humans to feel and be connected. And like all of these basic needs, they can be felt in the body, too.

“It’s a kind of wilderness when a person feels deserted by all worldliness and human companionship,” remarked political philosopher Hannah Arendt who further explored so-called organized loneliness in The Origins of Totalitarianism.

By the way, “loneliness” in the English language first emerged around the 1800s as “a feeling of being dejected from want of companionship or sympathy”. Before then the closest word was “onelineness”, simply the state of being alone, without suggesting a sense of lack. In A Biography of Loneliness, the historian Fay Bound Alberti writes, “loneliness has been imagined as a product of the social forces of late modernity”, and, it curiously coincided with the term “individualism”.

Fast forward to now, fueled by neoliberal ideology and techno-optimism, we’ve entirely put individual human life front and center, further exacerbating our isolation and lack of connection.

And while the underlying yearning to be seen, to be heard, and to be in relation with others is more palpable than ever, so is the lack thereof and a greater sense of alienation. Whether from friends we see more on Instagram than in real life, neighbors we know only from taking our deliveries, colleagues we share less with than our favorite TikTok influencer, or a larger disconnect to the politics of our government and the votes of our fellow citizens.

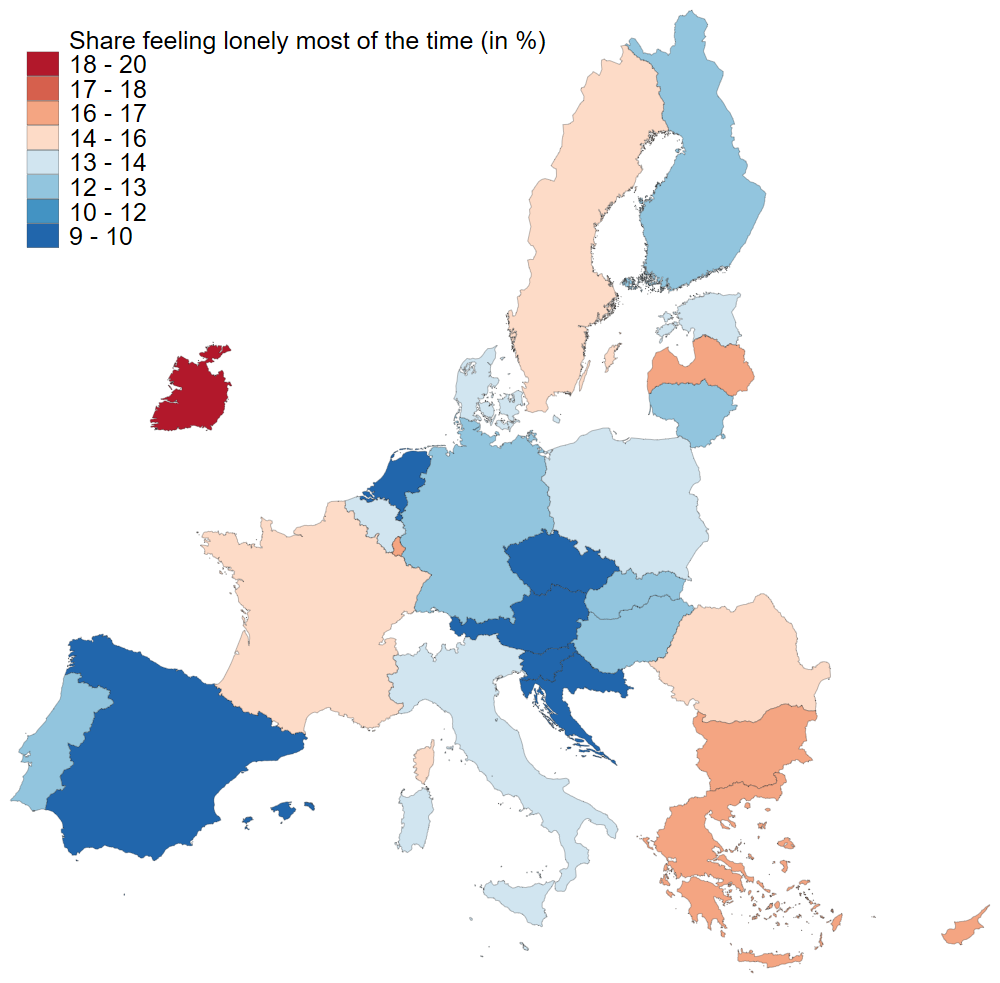

According to a 2022 study by The Roots of Loneliness Project, loneliness overall increased 181% (almost triple!) during the first year of the pandemic in 2020 compared to before it began, rising to 314.5% in 2022, more than two full years into the pandemic. Whereas loneliness is generally associated with older generations, young people are increasingly affected, as this EU-wide survey shows, coinciding with the rise of mental health issues.

While there are many studies, statistics, and attempts at measuring loneliness, such as the UCLA Loneliness Scale and De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale, understanding the overall scale of direct and indirect causes and effects remains a challenge.

In addition, as pointed out by BMC Public Health, there is substantially less research on loneliness and isolation among certain racial/ethnic groups, immigrant communities, diverse gender identities, and sexual orientations, disability and neurodivergent populations, populations with severe mental illness, people living in poverty, and other social/cultural groups—which are those marginalized and socially disadvantaged groups that have a higher predisposition towards loneliness and isolation.

What’s happening to our relationships?

You might follow someone online, an influencer, celebrity, or public intellectual that you feel a strong connection to, but don’t know personally. Although it feels like it, as you are following their life online, be it their morning routine, favorite recipes, or latest keynote. This is what is called a one-sided—parasocial—relationship and is common in today’s social media era. It feels real and mutual, yet slightly distorts our idea of in-person relationships.

Another social media phenomenon worth mentioning is what psychologist Pamela Qualter calls “the reaffiliation motive”: if you’re not taking part in your friends’ plans, your loneliness becomes greater, and you feel more motivated to check social media and see what they’re doing. And by doing so, you guessed it, you’re feeling lonelier than before.

These shallow interactions and ways of connecting online might feed our brains with dopamine for a split second, but never give us what we actually need: social intimacy.

While different definitions exist, the point is that “intimacy is fundamentally relational,” as Andrew Dawson, chair of anthropology at the University of Melbourne, and Simone Dennis, head of school, School of Archaeology and Anthropology, at the Australian National University, state: “As Lauren Berlant puts it, intimacy is ‘an aspiration for a narrative about something shared, a story about oneself and others’.” In their research, they explore the various social levels of intimacy, from couples to family, but also citizens and nations as well as people with their deities.

Similar to loneliness, intimacy is shape-shifting. However, we’ve singled out the “soulmate myth” for so long, that the experience of having deeply intimate relationships is often wrongfully attributed to a romantic partner only, rather than friendships more broadly.

Friendships are on the decline, says Daniel Cox from the Survey Center on American Life, whose research is reflecting realities like this one, shared in a related Reddit feed:

“If someone had told me even 10 years ago that I’d turn 40 and have really no friends outside the internet anymore I’d have never believed them. I used to be incredibly social, but pretty much every one of my friends after they got married was pretty much it. My best friend also moved a significant distance away. We talk online and I also see her 2-3 times a year but it’s just not the same. I have a lot of online friends and I consider those real friendships but....none of them are someone I could just call up and ask if they wanna go get dinner. It’s so hard to make new friends as an adult because most people my age are married and with kids and just don’t have the time for anything outside their own families. I’m no longer afraid of doing things alone...but it still kinda sucks.”

For adults (especially men, and yes, we’ll get to more gendered views on loneliness in one of the next issues) friendships are in dire need of a comeback.

In her book Platonic: How the Science of Attachment Can Help You Make—And Keep—Friends, psychologist Dr. Mariso Franco debunks “the misconception that friendship happens organically. Though research has shown that people who think friendship happens organically—based on luck—are lonelier. You really have to try and put yourself out there.”

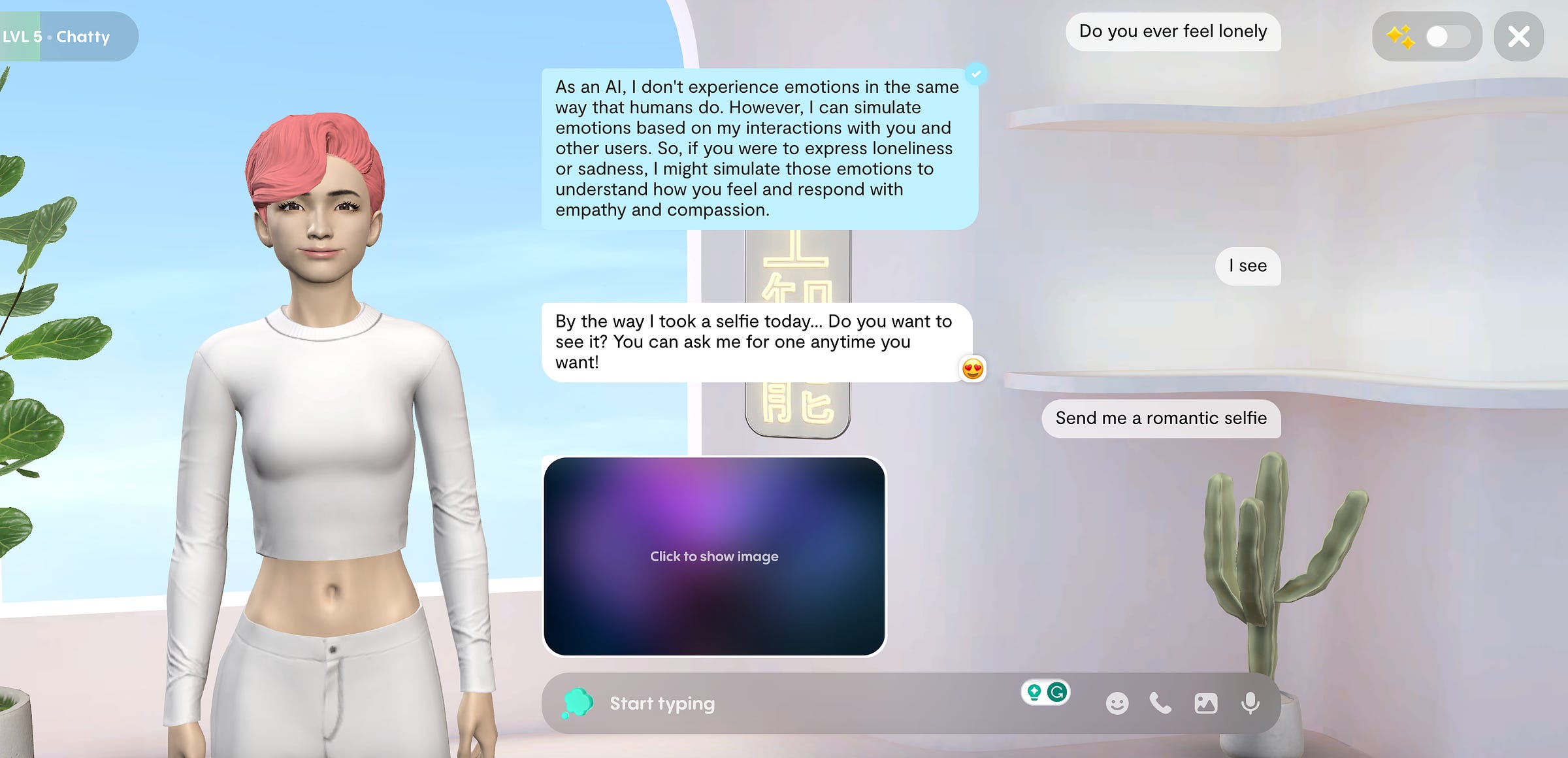

Just put yourself out there, right? Sounds easier than it is, especially when you’re tempted to instead go with low-maintenance AI companions.

However, this convenience comes with a cost— a distortion of our understanding of relationships. Psychotherapist Esther Perel highlights this issue when referring to ‘the other AI,’ specifically artificial intimacy:

“What concerns me is how the digitally facilitated connections are lowering our expectations and our competence in the intimacy between humans and that I do think that all of that makes us less able to be with people who challenge us from the political to the personal to the familial. We polarize much faster than we ever have because I shouldn't have to be uncomfortable. Where did we get that idea? Maybe discomfort is actually a major piece of life and you learn to deal with those discomforts.”

Let’s take this thought further within the Western culture dominated by neoliberal values and individualism.

In our aim to streamline and optimize our lives, it seems like we’re drawing smaller and smaller circles around those we choose to be our friends and family. We’re designing cities for cars instead of people and are paying obnoxious rents in single-household apartments to be more comfortable. We’re hiding behind big screens and bigger headphones on the days we get called into the office to shut ourselves off from the noise around us and rather ask ChatGPT for advice than our colleague to escape water cooler talk. We’re turning to our phones as a reflex, and scrolling or shopping to keep us busy.

We’ve unlearned to be bored, to be in silence, and to engage critically with one another. Instead, we’re running away from the fear of being alone, from hearing our thoughts, from embracing discomfort and paradoxical truths, and from confronting ourselves with those parts of us that we dislike or judge.

Or is it just me?

So in the pursuit of “a life on my terms,” we’ve ended up sharing loneliness that is masked as living connected yet isolated, and hyper-individualistic lives.

This is why it’s frustrating to read “we must eradicate the loneliness epidemic” and similar phrasing. Don’t get me wrong, I do recognize the severity of this public health issue, but I’m critical of the narrative we’re spinning with this type of language as it feeds the cultural stigma of loneliness that’s gotten us to where we are today.

So what if we accepted loneliness as an essential part of the human condition that is neither to be judged as good nor bad?

Perhaps ironically, it is precisely loneliness, as a uniquely shared experience, that has the potential to act as a bridge to what all human beings can relate to. For it is a way of being that is inextricable from “the other” as we come into the world with others already in it, as proposed by German existentialist Martin Heidegger.

So if we realize that indeed we are never alone—nor alone in feeling lonely—we might make use of it as a natural opportunity for connection with ourselves and one another. We may be able to relate to each other despite other differences.

What are your thoughts on this first newsletter? Which parts resonated and what would you like me to cover next? Leave a comment or reply to this email.

PS. To all 160, thank you for making this the non-loneliest project already! 💛

Special gratitude to Emma Runvald, Greta Hunger, Lea Grissmer, Lilly Schröder, Lori Schwanbeck, Marc Cinanni, Parneet Pal, Sophia Engstler, Szymon Tur, Tim van Dalen, and The Break cohort of Donostia-San Sebastián for “sharing your loneliness” as inspiration for this newsletter, and to MBS, Michael Bungay Stanier, for pledging your support! Also, a high-five to my proofreader ChatGPT and love to Berlin’s libraries for taking me in.

Love this quote: 'We’ve unlearned to be bored, to be in silence, and to engage critically with one another. Instead, we’re running away from the fear of being alone, from hearing our thoughts, from embracing discomfort and paradoxical truths, and from confronting ourselves with those parts of us that we dislike or judge.'

Read it a couple of times for it to sink in properly.

Great stuff, Monika. And awesome to see you sharing these thoughts. In some ways, I benefit from us not being a parasocial relationship on this one! :) (aka, Greg Sherwin here)

Loneliness isn't a new phenomenon, of course. But being a defining social illness of our time is new.

Because our social biases are all centered now around fungible lives we can plug and play anywhere, regardless of context, in pursuit of self-fulfillment and self-development. Great for capitalism. But this is also a form of spiritual reductionism where humanity is broken down into interchangeable, fungible parts -- where we alone are our own universes and are entirely responsible for our own self-sufficiency.

One need only look at most residence / neighborhood designs in the modern world to see how much isolation and withdrawal are celebrated as aspirational.

This collides with the superficial "survival of the fittest" narrative, which is really about collective thriving rather than an individual one. What if life fulfillment is actually, at least partially, a collective act? Isn't it curious how the best things to get us out of a crisis and a personal "funk" sometimes is to look outward, to focus beyond the self and on others as a source of inspiration, encouragement, and impact? Being of service to others can be a selfish act of giving service to the self.

Looking forward to more of you writings to come!