The Politics of Loneliness

Navigating Our Minds and Hearts Amid Rising Authoritarianism and Declining Trust

As I began contemplating loneliness, it struck me that it might somehow be connected to our current political divisions and the rise of authoritarian populism of the past years. So I delved in—and turns out, that there are numerous links between loneliness and politics, revealing the aching state of our societies on a deeper level.

Especially since the outset of the pandemic, governments and policymakers around the world have stepped up in their efforts to address loneliness. The U.K. appointed a Ministry of Loneliness in 2019, followed by Japan in 2021. Just weeks ago, U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy and African Union youth envoy, Chido Mpemba along with 11 advocates and government ministers, formed the World Health Organization’s international commission on social connection.

While these initiatives have garnered praise in public discourse, critical voices have emerged, too. Notably, the U.K.’s Minister for Loneliness, Stuart Andrew, faces scrutiny for one of his latest campaigns aimed at engaging students to talk more with each other—without investing in any actual infrastructure. With a marketing budget of £445,000, it raises suspicions of being mere lip service.

In the U.S., former intelligence analyst and author of The Weaponization of Loneliness, Stella Morabito vehemently criticizes U.S. senator Chris Murphy’s National Strategy for Social Connection Act. She questions Dr. Vivek Murthy’s intentions, arguing that social isolation is perpetuated by identity politics, political correctness, and cancel culture, all prevalent in government, academia, and the media.

This raises the question: To what extent and in what manner should politics address loneliness and social isolation?

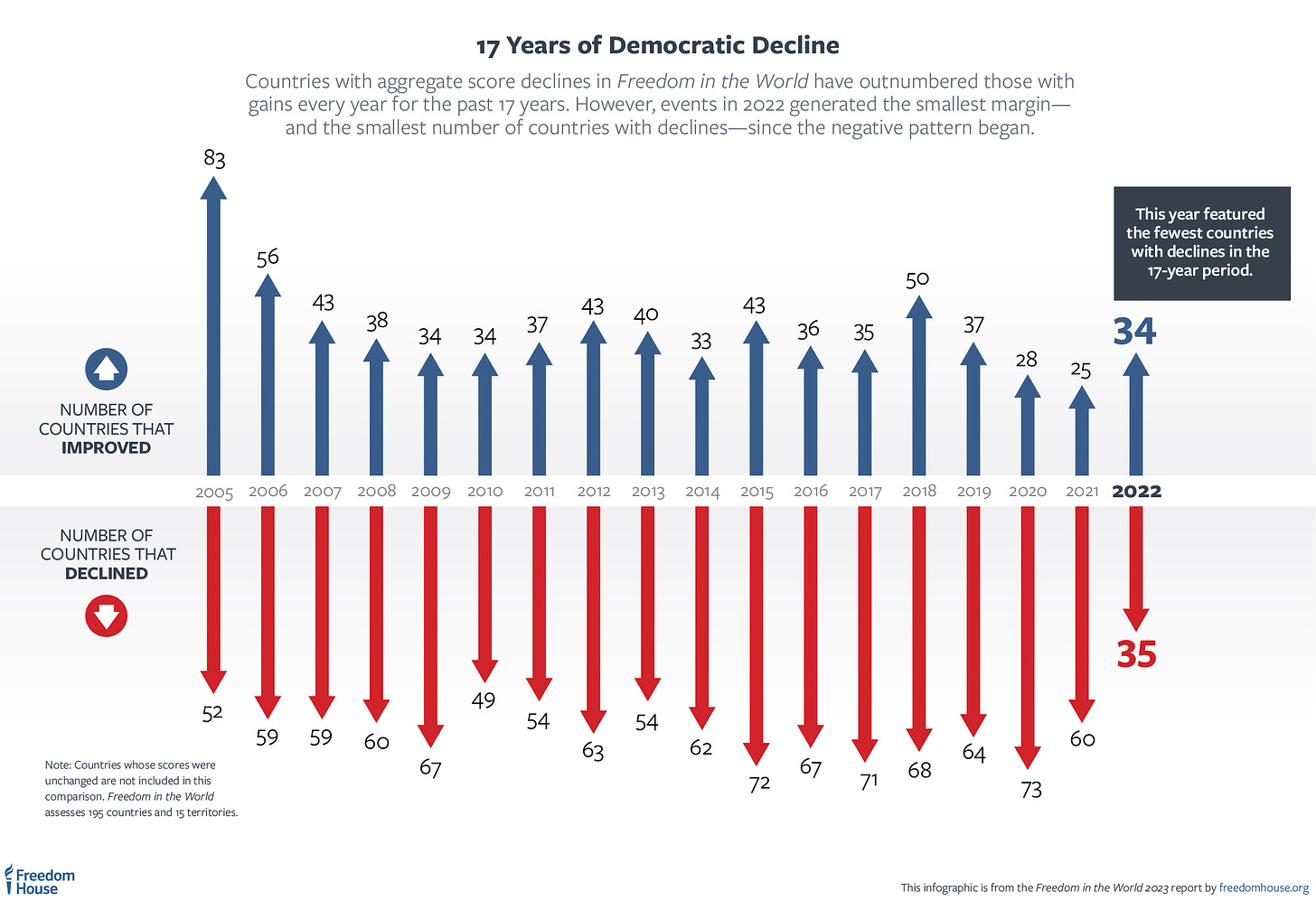

While navigating this complex question, it’s essential to realize that the surge in loneliness and social isolation is directly linked to the politics of distrust and othering, factors that have fueled the rise of authoritarian populism and, correspondingly, the decline in global democracy.

In 1951, political philosopher Hannah Arendt wrote in The Origins of Totalitarianism: “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e. the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false no longer exist.” Although we no longer live in Stalin’s Soviet Union, Hitler’s Nazi Germany, or Mao Zedong’s People’s Republic of China, parallels to today’s reality are evident.

Beneath the surface of superficial relationships, hyper-individualism, and a yearning for meaning, we appear to be losing this “reality of experience” by thinking critically. Arendt would argue that thinking is fundamentally democratic.

In our technocratic societies, we’ve succumbed to the monopolies of autocratic tech oligarchs. They reinforce our post-truth culture, where facts are devalued, and terms like ‘decolonization’ can face arbitrary censorship from one day to the next.

We’re numbed by the infinite stream of headlines, posts, and reels, making it almost impossible to form a clear thought before expressing opinions. Because ultimately, that’s what it’s about these days. Similarly to our rush for quick fixes, we rush to broadcast unfinished thoughts, pressurized to take sides, judging without thinking. We refresh our inboxes while our colleague is trying to bring up something that is important to them or pretend to listen to a friend while thinking about the next urgent topic we want to discuss.

In fifteen years of research into conversations between therapists and patients, for example, professor of clinical psychology, Mattias Desmet found that if one person stops talking, the other typically takes over in fewer than 0.2 seconds, even mid-sentence. For comparison, the traffic reaction time is approximately one second, five times longer. Desmet notes, “In real conversations, people's bodies constantly resonate with each other. The facial and body muscles of the listener contract in the same way as those of the speaker, and the same areas of the brain are activated.”

In his book, Psychology of Totalitarianism, Desmet warns of a new “technocratic totalitarianism” in which ethical principles become entirely obsolete. In this, “the masses believe in the story not because it’s accurate but because it creates a new social bond.”

So who’s capitalizing on the escalating loneliness of society? The populist leaders of recent years.

As early as 1992, researchers identified a correlation between social isolation and votes for the far-right Front National’s Jean-Marie Le Pen in France. In the Netherlands in 2008, people with less social trust were more likely to vote for the nationalist right-wing populist Party for Freedom (PVV). This trend was reaffirmed in the recent Dutch elections, which resulted in the victory of party leader Geert Wilders. Matthis Rooduin, associate professor of political science at Amsterdam University, succinctly summarized it: “When you look at the electorate of the PVV in general, it consists of people who experience more difficulties getting by. They are more lonely. They feel that they are being neglected. They have tough lives basically, economically but also culturally.”

In a similar vein, a 2016 poll by the Center for the Study of Elections and Democracy in the U.S. showed that voters for Donald Trump reported fewer close friends, fewer acquaintances, and less time spent on a weekly basis with both. They, too, were significantly likelier to respond with “I just rely on myself” to the question of where they’d turn to for help with challenges, ranging from child care to financial assistance, to advice on relationships, or to getting a ride.

Curiously, a recent study focusing on European parties found that people with a weaker sense of social belonging at the individual level tend to vote for right-wing populism, but not left-wing populism. Emotions related to loneliness, such as anxiety, insecurity, and the need for connection, align closely with the political ideology and narratives of right-wing populism, centered around a “returning to stability” nostalgia.

Analyzing the strategies of populist authoritarian leaders reveals their talent in creating a sense of community and belonging. Economist Noreena Hertz, in her book, The Lonely Century, notes this in the context of Trump’s rallies of branded gears, chants, the “we” statements, endless appeals to the collective, a “kind of communion”, similar to Alternative für Deutschland rallies, Spain’s right-wing populist Vox, Italy’s League “big family” and rhetoric of “Mamma, Papa, friends”, others.

In Argentina, newly elected far-right populist president Javier Milei, also known as ‘el loco’ loves shouting “Viva la libertad, carajo!” (Long live freedom, damn it!) during his speeches. Proclamations like these and the respective politics appropriate the certain authoritarian sense of freedom grounded in hyper-individualism, excluding the notions of solidarity, community, and care for each other.

As mentioned before, this narrative aligns with neoliberal values, further intensifying our isolation and lack of human connection.

The root of this phenomenon lies in the fact that right-wing populism thrives on a politics of othering. By creating a division of “us” and “them,” whether concerning immigration or the COVID-19 virus, a quick scapegoat is identified to exacerbate a toxic sense of belonging and togetherness.

The political strategies of current populist authoritarians are a manifestation of what Hannah Arendt termed “organized loneliness”—a state of feeling abandoned, isolated, and cut off from others and the world. In today’s day and age, it disrupts people’s relationship with reality as ideologies fueled by Big Tech’s mechanisms and artificial intelligence, strip people of their ability to think, discern, and make meaning for themselves. Instead, the allure of an alternative reality beyond everyday life keeps people captivated, and, ultimately, leaves them feeling more lonely.

To understand how the perception of the self and others can be altered, let’s turn to neuroscience, which suggests that loneliness isn’t rooted in a general aversion towards social interactions but in biases in our thinking. Those who experience loneliness tend to have a negativity bias, pick up negative social signals, expect rejection or bad intentions from others, and have a low sense of self-efficacy.

Now, place this in the context of the post-truth information age, social media increasing perceived isolation, AI’s influence on our well-being, and the overall atomization of society.

You get the picture.

So, as government leaders become involved, their policies must acknowledge the deeper intricacies of loneliness—not only as a public health issue but as one that signals the further perpetuation of divided societies, the politics’ insufficient scrutiny of big business, especially in tech, and the reality of many people feeling neglected, abandoned, and distrustful not only towards institutions but also towards each other.

I would argue that with the latter, there’s even more at stake. Losing trust in each other leaves us vulnerable to contempt and cynicism—which, as musician Nick Cave wrote once, “are the most common and easy of evils.”

Instead of giving in, we can begin small.

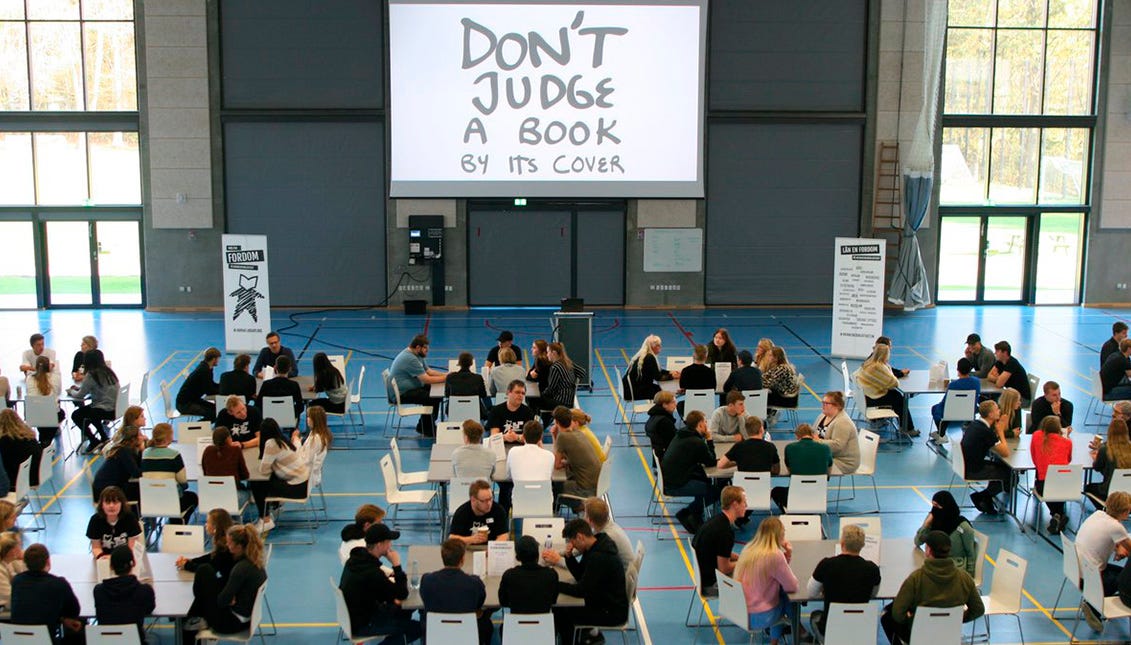

Remove your headphones and listen again, so loudly that you’re burning calories, even when there are people behind you waiting in line at the grocery store. Talk to strangers, support a community cafe, reconnect with your neighbor, host your own holiday season event, or rediscover the basics of dialogue again, by participating in The Human Library, designed to challenge stereotypes and prejudices.

Or, instead of leaving it up to politicians, actively engage in a citizen assembly to reimagine democracy and take charge of driving change in your community.

Finally, intentionally seek out moments of aloneness to reconnect with your thoughts, needs, and feelings, detached from the noise and constant stimulation. Whether through a walk in nature, meditation, writing, making music—or simply, savoring silence.

While these interventions don't aim to ‘cure’ loneliness, they can help us embrace and understand our shared experience. In doing so, we interpret its signals as prompts to heighten our awareness of what is most precious to us: our ability to feel, think critically, discern truth, engage in dialogue, and resolve conflicts nonviolently. By opening our hearts a bit more than required, we nurture these essential human skills that are slipping away.

Ultimately, it’s crucial to preserve our human condition of plurality, which exists because of our differences in each other.

Want to start with something small to embrace those essential human skills again—and come together in our shared loneliness?

Join our first community exploration on December 14 in person in Berlin (get a ticket) or December 19 on Zoom (sign up for free). It would mean everything if you showed up!

And how did this Sharing Our Loneliness edition resonate with you? Leave a comment or email me, it always makes my day to hear something back from some of you, whether here, on LinkedIn, or Instagram. Thank you for your support and ways of sharing.

With love,

Monika

Great article, Monika. By coincidence (or maybe by serendipity?) I tuned into a webinar yesterday - 'Can we win the fight against fake news? Mapping solutions to the disinformation crisis' - which was about the growing tide of disinformation here in Australia, the atomising effects of NewsCorp on our sense of community, the othering politics deployed to boost the No vote in our recent referendum on whether Aboriginal Australians should have a voice to parliament, and the increasing number of Australians disappearing down consipracy theory rabbit holes. One of the panellists, Tyson Yunkaporta, said a really profound thing about people who are drawn into echo chambers and even conspiracy theories, that I think chimes with what you've written in your article. He said 'they've lost their home. We need to find them another home.'