Like ants and bees, humans are inherently “eusocial”, organized through cooperation and division of labor across generations. The crux of the matter: our individual efforts may be limited, but our collective unity defines our true resilience. Entangled with the world, as post-humanist Bayo Akomolafe put it, our greatest achievements—or downfalls—have never sprung from solitary endeavors. But despite our innate eusociality, our contemporary reality often finds us at odds, standing isolated and lonely.

Crucially, we must acknowledge that the link between loneliness and time spent alone is not inherently synonymous. Studies have found that the feelings of loneliness are roughly stable—and low—for individuals spending anywhere from 25% to 75% of their day alone. You would think that someone who spends the majority of their time alone would likely feel more lonely compared to someone surrounded by other people, but that’s not necessarily the case. What makes a difference is the desire for a specific connection rather than merely being around others.

In alignment with our eusocial nature, the Social Baseline Theory (SBT) shows that we will find it easier and less energetically taxing to regulate emotions and act when knowing others are around and available. They found, for example, that people’s brains would have a weaker threat response when holding a stranger’s hand versus being alone.

In today’s day and age of hyper-individualism though, the idea of relying on others is too quickly (and wrongfully) judged as co-dependence, connections matter more in quantity than quality, and close friendships are becoming rare.

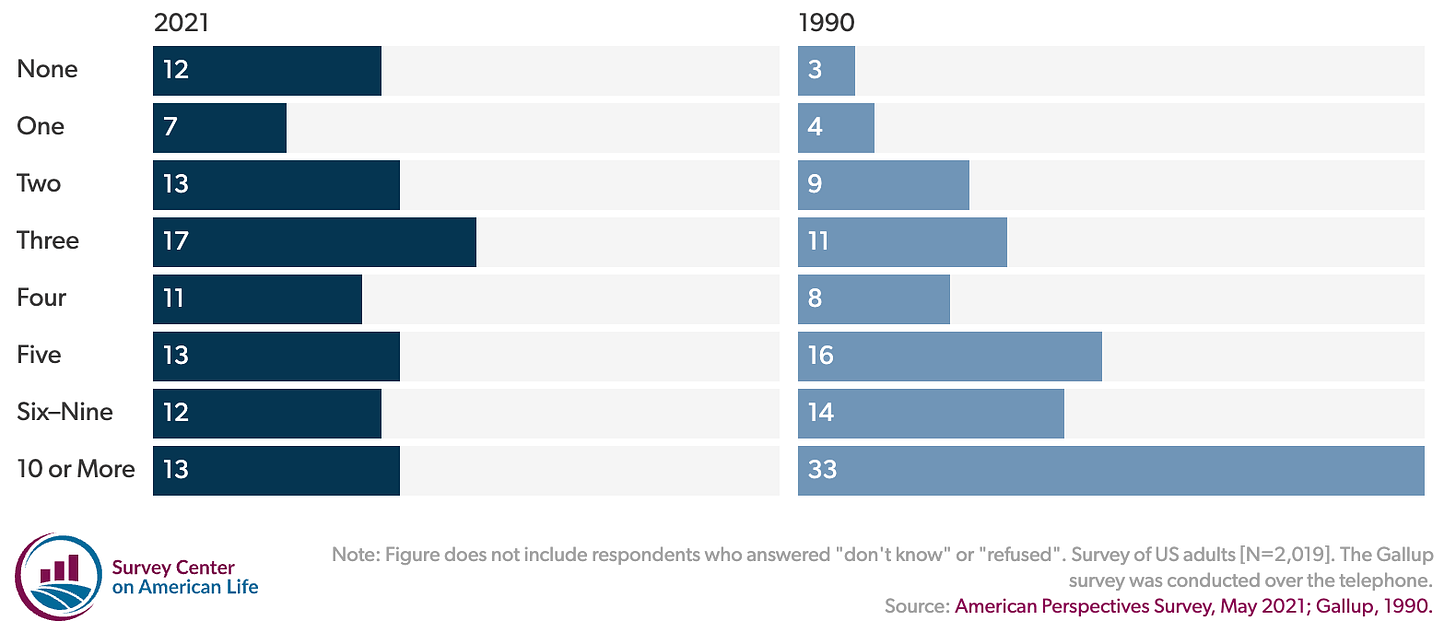

In the U.S., according to an American Perspectives Survey, between 1990 and 2021, the percentage of Americans reporting that they had no close friends at all quadrupled. For men in particular, the number had risen to 15 percent. In Europe, times spent with friends differ—with about 40% of people in Mediterranean countries like Greece or Portugal meeting daily, compared to 7% in countries like Poland, Austria, Latvia, and the Netherlands.

Consider “The Friendship Dip”—how our friendships evolve throughout life. According to

, we first experience this change in our late 20s and 30s usually due to moving from shared to individual and couple living arrangements, then in our late 30s due to diverging paths from family to careers, and then in the 40s and 50s, with a desire to rekindle still existing connections and cultivating new ones. As we age, the demands of our busy lives, combined with limited self-care (rather self-optimization) and the overproportionate time spent at work, seem to deprive us of what previous generations valued more: friendship.Nowadays, with dating apps (soon to be powered by AI as well) and social media, connecting online remains a balancing act between intentionally nourishing and mindlessly scrolling amid endless feeds of #couplegoals, #happytimes friend groups—and lately, #datingwrapped content.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

As Anna Lembke, professor of psychiatry at Stanford University School of Medicine, and the author of Dopamine Nation put it, social media has “essentially druggified human connection” contributing to all the features that make something highly addictive.

“For whatever reason, I crave connection. Then I go on Instagram or TikTok and it feels like I have connection because of all the dopamine. But in reality, I didn’t connect to anybody. I was sitting alone in my bed for six hours scrolling on Tik Tok.”

— Moss Jones, 26 in The Washington Post

Neurodivergent individuals face an even greater challenge in connecting meaningfully. As latest research states, unveils the distress experienced due to loneliness, given their sensitivity towards high-intensity social situations, such as being in large groups, around unfamiliar people, or in busy office environments. One autistic participant described her difficulties in forming friendships as an adult: “I’m trying to reach out, I’m trying to find my people, but it all still feels a bit hopeless.”

Then, there’s the reality of the over-glorification of romantic relationships and the “soulmate myth”, thanks to ideological standards created by Hollywood and social media. “When we view behaviors that create intimacy—being vulnerable, buying gifts, taking someone out on a date—as only appropriate for a romantic relationship, we end up limiting the potential of our friendships,” says Mariso G. Franco, Ph.D., an assistant clinical professor at the University of Maryland and author of Platonic, and makes a case for blurring the lines between the two.

Rather than burdening a soulmate with the expectation of meeting all your needs, cultivating a diverse range of friendships offers a more balanced support system—partly by allowing you to give support to others.

The perks are evident: those with strong friendships are more satisfied with their lives and less likely to suffer from depression, they’re likely to recover more quickly from illnesses and surgeries. Additionally, people with good friends report being less lonely across many life stages, including adolescence, becoming a parent, and old age. Friendships are so powerful that the social pain of rejection activates the same neural pathways that physical pain does.

Finally, friendship can be allied to politics, as German-American political philosopher Hannah Arendt understood it, namely that friendship with people you agree (and disagree with) has the potential to subvert power. As Jon Nixon writes in his book Hannah Arendt and the Politics of Friendship:

“Through our friendships, we learn to relate to one another as free and equal agents and, crucially, to carry what we have learned from those friendships—by way of the exercise of freedom and the recognition of equal worth—back into the world.”

Inspired by amor mundi, a love for the world for what it is, we may recognize that our problems will never be fixed, that there is no perfect theory or principle, but that politics are here to come together, look each other in the eyes, and critically discuss through our idiosyncrasies and differences. And to keep loving a broken world, Arendt suggested, we need to turn to oases—like friendship. The strongest of oases that keeps us from turning inward on ourselves and away from the world.

Final thoughts: Cultivating true friendship

Cherish small moments

Engage with the world around you—the barista at your favorite coffee shop, the pharmacist, or the cashier at your grocery store. A genuine smile, a thoughtful inquiry about their day, or a simple compliment can infuse warmth into these seemingly mundane interactions. Research suggests that conversations with strangers, often overlooked as awkward or shallow, can surprise us with unexpected enjoyment and genuine connections. Friendship, after all, can manifest in various forms, even in the subtle exchanges of day-to-day life.

Choose wisely

Embrace the principles of the “risk regulation theory.” The fear of rejection often holds us back, but we are less likely to face rejection than we imagine. Prioritize quality over quantity in your connections. Reflect on whether you thrive in one-on-one settings or group dynamics, and tailor your interactions accordingly. For introverts and neurodivergent individuals in particular, be mindful of your energy and recharge in ways that align with your needs. Lastly, respectfully part ways with friends who no longer align with your boundaries and goals.

Stick with it

Building close friendships takes time and dedication. Research indicates that it takes 30 hours of interaction to form a casual friendship, 140 hours for a good friend, and a substantial 300 hours for a best friend. Maintain a positive mindset, akin to the "acceptance prophecy," where you assume that others like you can create a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Reach out regularly

A recent study emphasized the profound impact of a simple text or email when reaching out to friends and acquaintances. You might think “Oh, they're too busy” or “I don’t want to bother them”, but the truth is that both parties often share these assumptions, creating a standstill. Break the cycle—especially when you haven’t heard from someone in a while, send a text or a (short) voice note!

Practice guesting and hosting

Step beyond your comfort zone—dine with strangers, attend events aligned with your passions, and skip the ones that feel primarily transactional rather than purpose-driven. Join a social club or host your gatherings to create purposeful connections. Embrace the roles of both guest and host, fostering an environment where connections can thrive.

Befriend yourself

Acknowledge your role in fostering connection—and become your own friend. Explore the truth of the story you tell yourself, the beliefs and values you hold or have outgrown, while prioritizing your needs before seeking connections with others. Over the past year, I've learned a lot (!) about my attachment style (anxious, obviously) and ways to regulate my nervous system, which ultimately has confronted me with behaviors I've been struggling with since I can remember. It’s only now that I’m beginning to make sense of these parts of me that ultimately impact my relationships across all aspects of my life.

Which of these ideas resonate with you the most? And how are you befriending friendships in your life?

Alternatively, email me with your thoughts or wishes for 2024 topics to cover! And befriend me on LinkedIn or Instagram if you feel like it.

Thank you to everyone who showed up at the first community gathering in Berlin and online! I’m humbled to feel the resonance of “sharing our loneliness”, and am looking forward to continuing to evolve together this coming year. Happy holidays!

Awesome, friendship seen from different perspectives!! The one that gives me a sensitive hug is the 'befriend you'. Because this is for me the best to be friend with likeminded people. ☆☆Rike